Present Tense: Photographs by JoAnn Verburg

The photographer JoAnn Verburg is enjoying a mid-career survey currently on display at New York’s Museum of Modern Art. Accompanying the exhibition is a handsome catalog called Present Tense: Photographs by JoAnn Verburg that spans her career since the early nineteen-eighties.

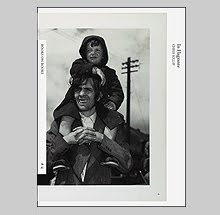

Verburg is an artist that came of age when most post-modernists were “using” photography as simply the final vehicle for their art to reach an audience. Interested in time and the translation of time in photography, much of her earlier work, explores portraiture through a series of images rather than by a single definitive one. By using the camera to describe a lateral panorama of images, she captures elements from each frame that bleed over into the next, giving the sense of a continuum of action and gesture. Many of these early images feature active members of the early eighties art world. This is an interesting fact as their presence when seen today, as well known artists, tends to introduce a different dynamic to the pieces as perhaps originally sought.

In her next project, she pursued a series of images made of people suspended in pools of water. Shot from a vantage point akin to hovering over her subjects, they defy gravity in an upended world that disorients viewers with their vertiginousness. They often refer to classic images common throughout art history of floating cherubs and images of grace but they do not simply mimic but offer a modern image, classic in form, to current emotional states.

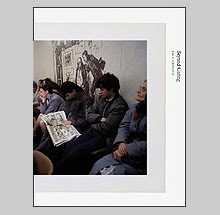

The work that excites me the most is the work Verburg has done describing the domestic life with her husband, the poet, Jim Moore. Photographed in the 1990’s, she utilizes single image as well as diptych and triptychs to describe aspects of her home life. Made often while Mr. Moore is reading the newspaper or sleeping if we were to gauge his life based solely on her pictures we should all be gifted to live a poet’s life. His is one waiting for the muse to appear. Moore however is Verburg’s muse and Verburg’s love of his image is apparent to us in the care in which she looks upon him.

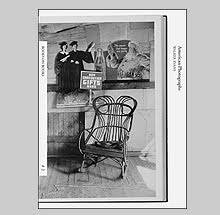

Though do not mistake these for pictures devoid of the issues of the “real” world. The domestic tranquility is confronted by the newspaper headlines and article headers that are sharply focused upon by Verburg’s large format camera. In essence, these are perfect descriptions of how most of us confront world problems and global tremors, through a newspaper or other isolating device. To carry that thought a bit further, to me the comfort at which the headlines in these pictures is experienced somewhat lances liberal political approach with an image of inaction. The headlines are read after we have enjoyed a café latte while sitting in perfect sunlight on our picture perfect garden terrace. It has the same feel as is common with characters from Woody Allen’s image of what Manhattan liberalism represents.

The draw of the show at the MoMA for me was a wall of these images displayed in an ordered but chaotic way whose sum created the most interesting dynamic. After seeing that arrangement of images to go back to looking at one image at a time was a difficult task.

Her latest work is a series of multi panel images of olive trees in Italy. By using the focus control of the large format camera, she isolates fields of clarity that playfully focuses on different planes within the frame. Though interesting and definitely seductive in technique, I was left a bit disappointed by my ability to see anything more than their beauty. (That seems like a sentence that would come from someone working something out with their shrink). Though there is nothing wrong with beauty per se, these images seemed more decorative than the rest of the show (and work in the catalog). Verburg has conditioned me to “read” more into her images, so for these, I haven’t figured my approach. The very latest work of handmade pyramids escapes me as well, but given that time is such a subject for Verburg, I figure I have mine as well.

The catalog, Present Tense is very nicely put together and fairly well printed. I find there is a very subtle cyan or green cast to many of Verburg’s actual images that is a bit more apparent here in this catalog. Present Tense: Photographs by JoAnn Verburg also includes a fine essay by Susan Kismaric, the show’s curator.

Buy online at MoMA